Blank

pages are the enemy.

If you want to consistent

generate compelling content, the trick is to ensure that there’s something

going on all the time, not just the moment you sit down and decide to start working.

To assure your process of creation isn’t driven and dictated by time pressure

alone. To insure that your instrument is finely tuned for the world to move

through you.

Which

means, you have to dig your creative well before you’re thirty.

George Carlin

was a thirsty guy. In a posthumous book about his prolific creative process, he

explained that his brain got used to the fact that casting about for new material

made it feel good. And so, it started networking on its own, making connections

and comparisons, and pretty soon there was an automatic process going on all

the time, one that left out unimportant or less interesting areas so it could

concentrated on areas it trained itself to passively look for.

That’s

far out, man.

But the

human brain loves this.

George

says it’s a goal seeking, problem solving machine. And by feeding into it the

parameters of what you need or want or expect, it starts to do a lot of work

without you even noticing. Because that’s what the brain does. It forms neural

networks. And if you train it correctly, areas of your brain will start to

communicate with one another as they notice ideas that belong together.

You’re

no longer working on material; the material is working on you.

This cognitive process called unconscious rumination.

Samuel Sinclair Baker popularized the term about fifty years

ago. Born to immigrant parents over a century ago, he became a famous

advertising executive in his first career, an original founder of Miracle Grow

in his second career, and a bestselling author of diet and gardening books in

his third career.

Prolificacy was literally second nature to him.

I bought his book, Your Key to Creative Thinking, at a used book fair for one dollar. And once I

read the back cover about his mental strategies to help people reach greater

heights of productivity than they ever thought possible, I was sold.

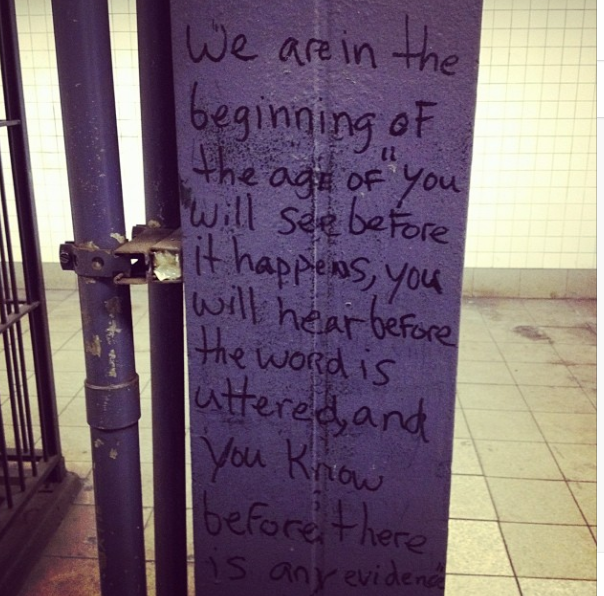

Unconscious rumination, he says, is when you let your mind

have fun occupying itself with a variety of ideas, so that the subconscious

impressions combine with your conscious efforts and realizations. You allow

your inner mind to get to work mulling over, sorting out, organizing and

categorizing material that has been previously absorbed. And over time, your

inner brain, that’s been working on a solution while you’ve been applying

conscious thinking in other areas, speaks up. That way, the idea you want

emerges at a time when the mental spotlight isn’t on it.

I’ve personally watched this process play out in my work as

a musician.

Twenty plus years writing songs, and I still find myself

dumfounded as to where certain lyrics and melodies and rhythms come from.

Apropos of nothing, I’ll be in my studio and spontaneously start strumming or

singing or tapping my foot in a really interesting way and say to myself, what the hell, where did that come from?

Unconscious rumination, that’s where.

Long before I stepped into the studio that day, my mind had been unconsciously

churning away, gathering pieces of melody and lyric together like a musical jigsaw

puzzle. Because the seed of any idea, sorting itself from others, may

take weeks or even years to germinate and come to the surface, fused with later

observations.

It only

seemed that it was instantaneous.

You’re no longer working on material, the material is

working on you.

Digging

your creative well before you’re thirsty, then, is a passive process. It’s an

unconscious experience that happens independent of your effort, since the brain

seems to enjoy working alone a lot of the time.

But you’re not completely off the hook.

You still have to accumulate reference files for your brain

to work on. And you have to make yourself hyperaware of unconscious rumination. And in time, you’ll soon find that consistently generating compelling

content won’t be as hard as people make it out to be.

Who needs a blank page

when you’ve got a bustling brain?