The creative process commences with input.

You build a framework for inspiration by living your life in

a way that your art gets done over and over. This helps you populate a unique

inspiration pool that nobody can replicate, solidifying the originality of your

work, guaranteeing you’ll never get blocked.

The creative process continues with throughput.

You establish a discipline for getting your ideas to ground

zero, assuring that everything you know is written down somewhere and processed

into the system. This helps you accumulate a creative inventory that becomes

the raw material everything you make.

The creative process completes with output.

You initiate a series of active and passive rituals,

practices, environments and mental subroutines that make creating a natural

extension of your personality. This helps you turn seeds into forests and more

fully flesh out your work.

But once you’ve done all that, once you’ve translated your

brief moment of inspiration into a robust collection of related concepts that

are just begging to become something bigger, it’s time to stop creating and

start judging.

You have to look for

an organizing principle.

I’m reminded of a fascinating interview I heard with Conan

O’Brien about his life as a late night talk show host. He told the interviewer

that his show was the organizing principle of his life. That it was the iron

rod in the center around which everything else gravitated.

Your work is the same way.

Whatever it is that you’re creating or crafting or

communicating, there has to be a core assumption, a central reference point, a

guiding pole, which governs action and allows everything else in its proximity

to derive value.

For two reasons:

First, the organizing principle keeps you on track as the idea creator. It makes it easier to

align, organize, remember and deliver everything you’re trying to communicate.

Otherwise you’re just vomiting.

Second, the organizing principle keeps your audience on

track as the idea consumer. It makes it easier to listen, digest, remember

and apply everything they’re trying to receive. Otherwise they’re just inhaling.

The question is, how do you find it?

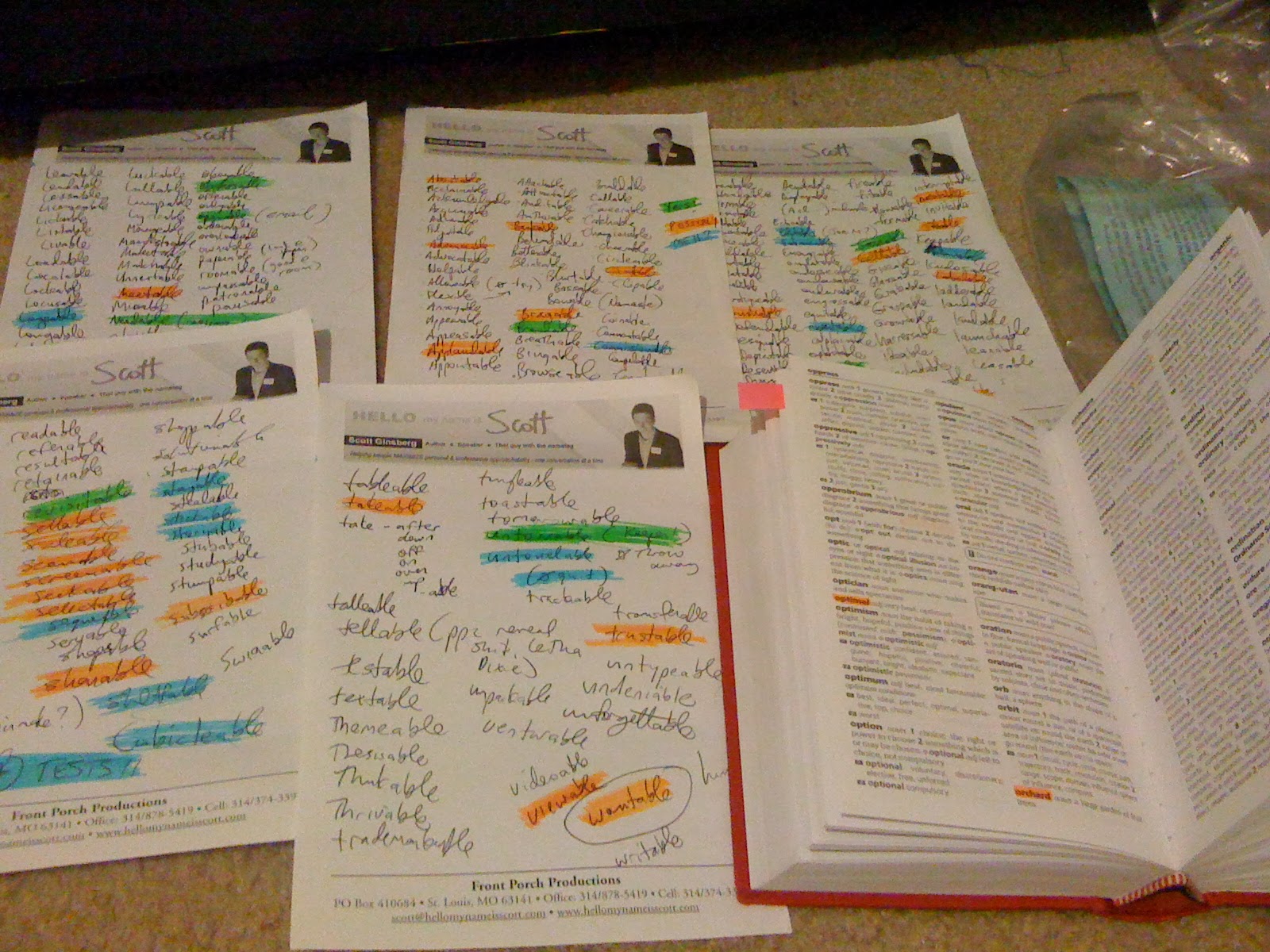

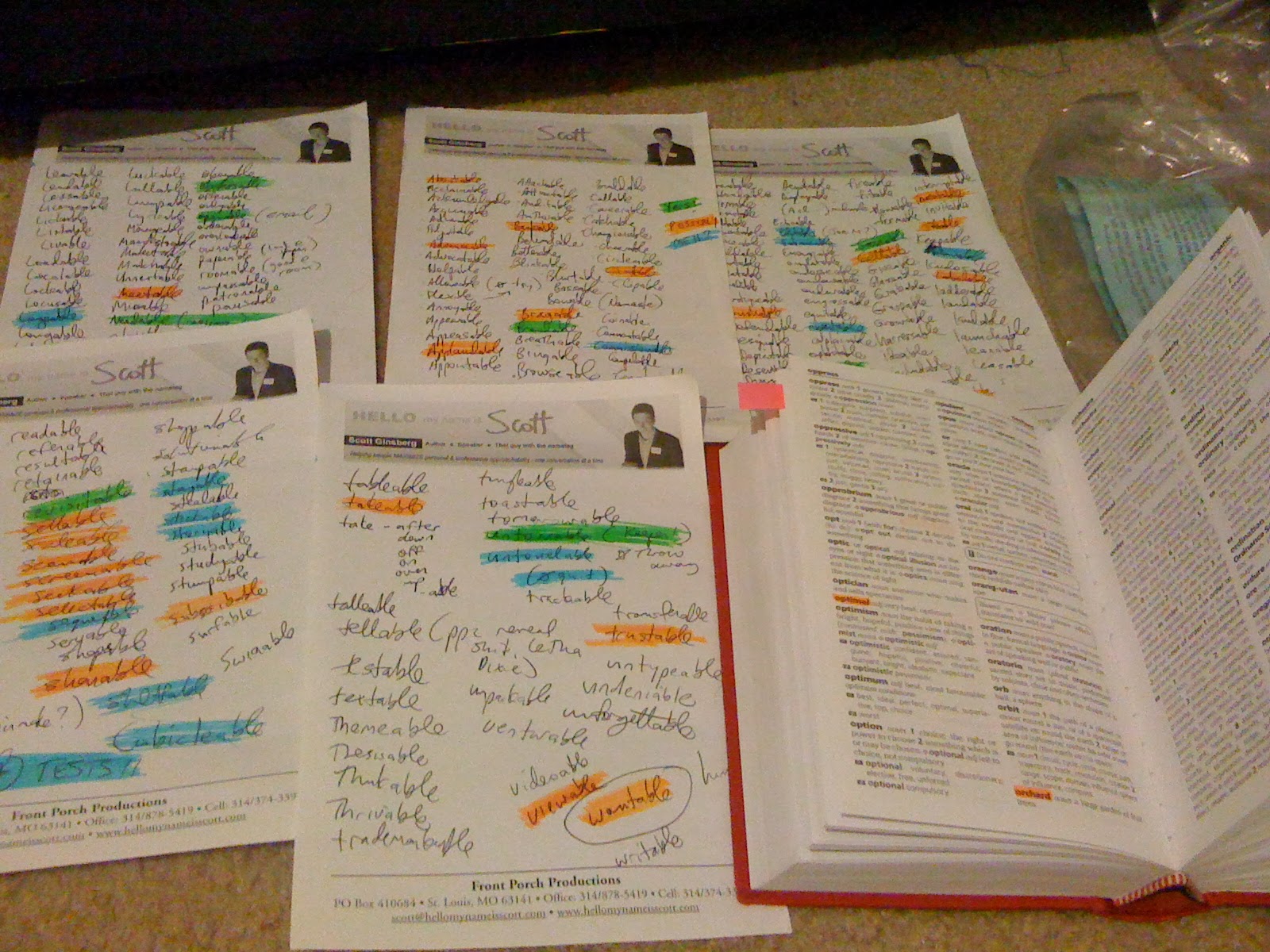

When I wrote my first book, I remember hitting a wall. Most

of the writing was done, but when it came to the process of organizing the

material, I was stuck. So my mentor suggested that I buy a box of index cards, write

down one idea per card, scatter them on the floor, stare at them in silence for

a few minutes, and then allow the inherent geometry of the ideas take shape.

It sounded like an interesting experiment, so I gave it a

shot.

And I’ll never forget what happened next.

The ideas started to take on a life of their own. They started

to find each other.

And as I surveyed hundreds of index cards on the carpet, I had

this feeling that they weren’t just speaking to each other, they were speaking

to me, too. Announcing that they had done the work of sorting themselves, and

all they needed was a helping hand to rearrange them into specific piles.

Sure enough, those piles become chapters, which ultimately

became the organizing principle of my book.

Who knew it was that easy?

It’s like Alan Fletcher used to say, he always knew he was

onto something because instead of him looking at the subject, the

subject began looking at him.

Since that initial experiment, I’ve run that notecard exercise

hundreds of times, both in my own work on books, speeches, training videos and

other creative projects. But I’ve also taught that exercise to my clients and

workshop participants, using a diverse range of topics. And in my experience, it’s

the single most effective method for identifying the organizing principle of a

creative project.

Because it’s not an accident, it’s self-organization.

Neuroscientists purportedly discovered this process in the

forties and fifties, although its conceptual roots most likely date back to the

ancient Greeks. Regardless, the working definition of self-organization is a process where some form of global order or

coordination arises out of the local interactions between the components of an

initially disordered system.

In my case, the “local interactions” were the hundreds of

individual notecards, and the “global order” was the dozen or so piles.

But the most popular examples of self-organizing systems

include the creation of structures by social insects like honeybees and ants, the

flocking behavior of mammals like birds and fish, and of course, the ultimate

self-organizing system, the human brain.

The book Brain Based Therapy with Adults said it best:

“Neuroscientists view the brain as a self-organizing system

that is malleable and plastic. The brain continually pulls itself up by the

bootstraps, becoming more organizing and patterned over time. This habit of

neurons organizing themselves into networks of thousands and even millions of

cells is a psychological phenomenon, and it is impossible to overstate the

significance of this simple idea.”

It’s a beautiful thing. There truly is harmony within

hierarchy.

The exciting part is, once you identify the organizing principle,

you immediately start to watch your project or idea or creation start to take shape

and acquire real structure and meaning and weight.

In his final book before he died, George Carlin explained that initially, ideas

come together the way galaxies do, they just naturally clump, simply because

they’re related, like an extended family of ideas around a general topic. But

over time, they become parts that fit and function together, which you then

gradually form into a whole.

And that’s when the work transitions from idea to execution.

So the next time you find yourself complaining, “I have

enough ideas, but now I need to figure out what to do with them,” consider

running some variation of the index card exercise. Put your brain to work to

find the inherent geometry of your project. Let the ideas talk to themselves,

and then let them talk to you.

Before you know it, the organizing principle will stand up

and reveal itself.

And you’ll be off to the creative races.