The process of fully fleshing our your work hinges upon movement

value.

It’s the discipline of recognizing conceptual beginnings, witnessing

ideas in their nascent state and thinking to ourselves, hey wait, I think there’s something here, and then using that

moment of conception to spawn as many creative offspring as possible.

Turning a seed into a forest, essentially.

This is the crucial process that separates the creatively

blocked from the consistently prolific. It’s the intersection of metaphorical

thinking, memory jogging, strategic researching, creative stretching, structured

brainstorming and rabbit hole venturing.

But once you hone this skill, once you master the art of

movement value, not only will your creative output multiply, but the people in

your life will start bringing their seeds to you, begging you to help build

their forests.

Let’s do one together.

Last night, the subway line by our house was shut down for

maintenance. Naturally, we didn’t realize that until after we’d walked ten blocks to the train station. And if you’ve

ever lived in a big city without a car, you know how deflating that moment can

feel.

By the time we figured out our alternate route, estimating

that we would arrive hour late to our destination, my wife and I took one look

at each other and said, screw it, we

don’t care anymore, it’s getting late, let’s just order barbecue takeout and

watch a movie.

Stupid subway.

But on the walk back home, I pondered the experience and

wondered if it pointed to a more general principle. And I said to my wide,wow, technology is, like, both the great

enabler and the grating disabler.

Hey wait, I think there’s something there.

Here we go…

Domain transfer. What else is like this?

Internet access. When the cable goes out or your cell phone

dies or your laptop runs out of battery power, you’re screwed. Helpless.

Completely idle. Just like we felt with the subway. Which is interesting,

considering rapid transit dates back

over a hundred and fifty years, while the internet only dates

back only years. Perhaps the human dependency on any form of

technology, be it transportation or digital communications, can be a dangerous

vice.

Motion picture. Did someone make a movie about this?

Timed to correspond with Europe’s Internet Week, advertising

agency Mother London made a short documentary about a “disconnection

experiment.” What would happen if five digital natives were forced to go cold

turkey for a week? The camera crew followed the participants throughout the

week, documenting their experiences, both good and bad. Watch the full

documentary called No Internet Week.

Case study. Is there scientific research behind this?

In a recent study

published in the Journal Computers in

Human Behavior, researchers investigated the dark side of the smartphone trend.

The authors examined the link between psychological traits and the compulsive

behaviors of smartphone users, and looked further into the stress caused by

those compulsive behaviors. And sure enough, this study is only one of dozens

that have been conducted.

News piece. Has the media reported on this?

I found an unbelievable news

story about a young man who dropped his cell phone into the freezing

cold Chicago river. He clambered over the railing in order to get it back and fell

into the water. Then two friends jumped into the icy river after him. Long

story short, the man who dropped the phone died in the hospital. And the friends

who jumped in to save him were said to be in critical condition. Wow. Is

technology really worth risking our lives?

Word study. Are there any interesting definitions or

etymologies?

Technology is such a common word, idea and daily experience,

that most people have never thought to look it up in the dictionary.

Turns out, the word derives from two Latin terms, techno, which means “art or skill,” and legin, which means “to speak.” Interesting. And the definition of

word can refer to the creation and use of technical means and their

interrelation with life, society, and the environment. But it can also refer to

the terminology and nomenclature of an art or science. Then again, technology

can mean any scientific or industrial process, invention, method, or the like.

Internet meme. Who else feels like this?

Tumblr has tons of blogs talking

about technology mishaps and addictions. I found posts that said, “My internet

was down all day and I died several times … When both the internet and cable

signal are down, times are indeed dire … If your subway is broken down, the taxi

driver may be a horrible person who charges you a crap ton for each block.” And

that’s just one social network.

The list goes on forever.

And depending on how much time you have, how fully you want

to flesh out your idea out and many creative offspring you want your seed to

produce, you might also consider the following categories:

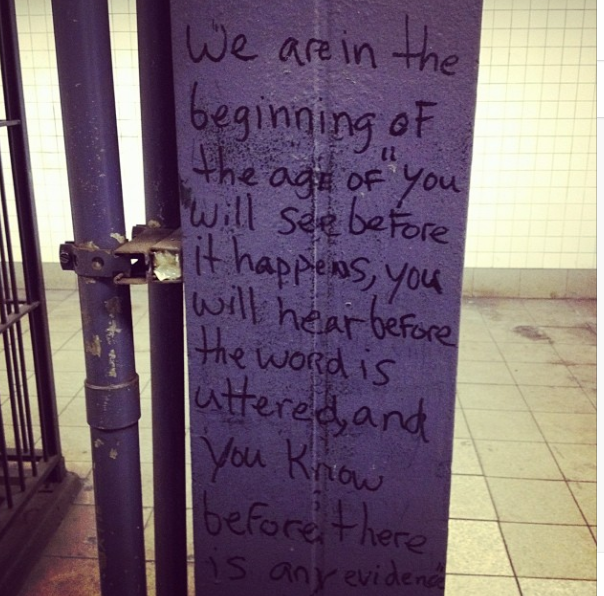

Personal examples, memorable moments, public signs, song

lyrics, movie lines, urban myths, scientific constructs, historical references,

people you know, famous hypotheses, possible inventions, pop culture references,

parallels in nature, poignant warnings, business personification, human

absurdities, childhood memories , iconic images, classic jokes and common

sayings.

And don’t forget universal human motivations, theoretical

concepts, interesting patterns, personal stories, immediate actions people can

take, powerful insights, noticeable numbers, objective observations, public declarations,

inspiring invitations, powerful questions, palpable consequences, something

you’re not okay with, something that offends your sense of order, practical

implications, real world applications, possible related situations and

geographic locations.

That’s movement value.

Turning a seed into a forest.

And the exciting part is, it all started with that ground

zero experience of a broken subway train, and thinking to myself hey wait, I think there’s something here.

Tom Clancy was the bomb.

Tom Clancy was the bomb.

Sundance knew he shot better when he moved.

Sundance knew he shot better when he moved.